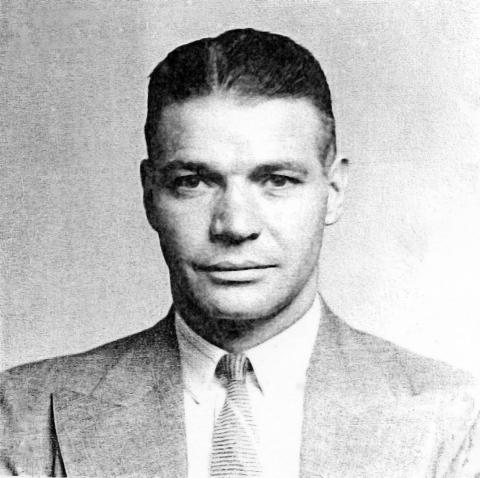

Claud Charles Holsten

Pre-WSC Background

Claud Charles Holsten was born on January 31, 1909 in Alma, Missouri to Charles W. Holsten and Mary Charlotte (Lottie) Bell. He had an older brother, Lyman, born in 1903, and two younger sisters: Juanita, born in 1910, and Hazel, born in 1912. Charles Holsten was a farmer, an occupation his son, Lyman, would also pursue in his adult life. The family relocated to Fairfield, Washington, a small farming community located thirty miles southeast of Spokane, shortly after Holsten’s birth, and both his sisters were born in Washington.

Holsten attended Fairfield High School, where he took part in the senior play, “The Whole Town’s Talking.” He transferred to North Central High School in Spokane in 1927, where he excelled in sports. He played both football and basketball during the fall of 1927, and baseball and track in the spring of 1928. North Central’s football team finished their 1927 season at the top of the city of Spokane’s standings, with a 3 and 0 record in city competition, and a streak of eight straight victories overall. They earned the title of “undisputed proprietorship of the 1927 city interscholastic gridiron championship.” Holsten played left end, and the North Central team drew a crowd of 10,000 people to watch them defeat their cross-town rivals from Lewis and Clark High School on November 24, 1927, the final game of their season.

Holsten’s skills on the basketball court were on display during his final season in high school. He was a letter man while at Fairfield, and he consistently maintained his status as a top scorer in the forward position during the 1927-1928 season for North Central. One of the few losses faced by the North Central team occurred on March 5, 1928, when they were defeated by the Y.M.C.A. team. Despite the loss, the close of the game was described as a “spectacular battle between Claude Holsten of the Indians and Dan Aukett, who played for Lewis and Clark this year.” Holsten scored three field goals in “55 seconds of the last quarter,” tying the score at 21. Aukett scored, then Holsten, followed by a “melee under the basket in the last moments of the game, Aukett knocked one into the cage for the last counter and victory.” Holsten’s play was the “feature of the game,” and he led the scoring with seven field goals.

The team won the city championship and competed in the state interscholastic tournament in Seattle, where they triumphed over Mount Vernon, 21 to 15, in their first game; Holsten scored five points. In their next game against Anacortes, their victory was so decisive the Spokane Chronicle wrote “…the Indians are now considered favorites to win the title.” Holsten scored six points in the 26 to 12 victory. In their final game of the season against Cheney, North Central claimed the state basketball championship crown, defeating their opponents 33 to 19. Holsten scored eleven points. The team was coached by legendary basketball coach Jack Friel, who would move to Washington State College (WSC) along with Holsten in 1928.

During the 1928 baseball season, Holsten stood out as one of North Central’s top hitters, and the team defeated cross-town rivals Lewis and Clark 12 to 7 in front of a crowd of 2500 people. Holsten graduated from North Central in June 1928.

WSC Experience

Holsten attended WSC from 1928 to 1932, earning 93 credits toward a degree before dropping out. He served three and a half years in the R.O.T.C., achieving the rank of Captain. He also belonged to the Sigma Chi fraternity. While at WSC, he continued to earn a reputation as an outstanding athlete as he did in high school. While he participated in football and swimming, he was a standout baseball and basketball star in college. In fact, a short biography left on the FindaGrave.com website calls Holsten out for his dedication to athletics, noting his studies were “secondary to athletics, and as such he was a ‘C’ student in college.”

Coached by O.E. “Babe” Hollingbery, Holsten participated on WSC’s 1928 football team, the team finishing with a 7 and 3 overall record, with the last two games dropped to U.C.L.A. and the University of Washington, respectively. Holsten played on the WSC freshmen team for the 1928 to 1929 basketball season under the tutelage of Coach Fritz Kramer. The “Kitten basketeers,” as the team was called, started off with a record of eleven victories in twelve starts, with Holsten the “mainspring” in the first WSC victory against the University of Idaho Vandals. In his sophomore year, Holsten made Coach John Bryan “Jack” Friel’s cut to play on the varsity basketball team. During pre-season, Coach Friel noted that prospects for the coming season were “none too bright.” The 1929 to 1930 team included Archie Buckley, “one of the most outstanding all around athletes developed at Washington State” and a fellow Fallen Cougar. Coach Friel himself, a former captain of the WSC basketball team and an all-conference player, would go on to become the winningest basketball coach in Cougars history. The high point of his coaching career came in 1941, when the Cougars went 26-6 and reached the NCAA tournament championship game, only to fall to Wisconsin 39-34.

Despite Coach Friel’s worries, the 1929-1930 team finished 14 and 12 overall, improving on the varsity team’s record of 9 and 14 the previous year. In a loss to Gonzaga, Holsten shone with thirteen points and almost brought the Cougars ahead in the final seconds of the game. In a WSC victory against Idaho, Holsten’s “dazzling shooting” helped propel the Cougars. By the end of January 1930, Holsten was the high scorer for the team, with a total of 120 points; he was second in the northern division Pacific Coast Conference (PCC). During this time period, Holsten was also nominated as Vice-President of the sophomore class for the semester.

The following year, Holsten was selected to the all-northern division Pacific Coast conference basketball first team. He remained one of the top three scorers for the Cougars, as well as among the top fifteen scorers in the state. The Cougars finished the 1931 season with eighteen victories against seven defeats, going ten and six in conference play for a second-place finish.

Holsten also played for legendary baseball coach Buck Bailey during the 1930 and 1931 baseball seasons. Bailey arrived at WSC as an assistant football coach but became a legend as its “colorful and winning head baseball coach,” from 1927 to 1942, then again from 1946 to 1961. During his coaching career, Bailey’s baseball teams won eleven Northern Division Titles, with the Cougars making two trips to the College World Series. While Holsten played baseball for Bailey in the spring of 1931, he also got married. He and Mabel Laura Cain, a graduate of Eastern Washington University, married on March 12, 1931 in Pomeroy, Garfield, Washington.

For the 1931 to 1932 basketball season, the Spokane Chronicle centered a photo of Holsten in his basketball uniform in the December 26, 1931 issue, describing him as a “rugged forward” and a “past master in the art of dribbling around a guard from the sidelines…” The Cougars went 22 and 5 overall, 11 and 5 in conference play for a second place finish. University of Oregon coach Billy Reinhart named Holsten to first team in the northern division as a guard. It would be his last season as a Cougar. Due to the responsibilities and financial pressures of married life, Holsten left WSC without completing his degree. However, in June 1932 he signed on to play first base for the Perry Street Boosters, an Inland Empire semi-professional baseball team, after fellow Coug Archie Buckley left the team so he could spend his summer in Pullman.

In addition to playing in the Inland Empire baseball league, Holsten also doubled as a coach and player for an independent basketball team, The Desserts, in Spokane. The Desserts, Inland Empire champions in the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) league in 1935, often crossed paths with Coach Friel’s WSC basketball teams in tournament play. Holsten’s team reached the Northwest championship tournament, where they walked away as the runners-up against all odds. For the 1936 season, Holsten predicted a stronger team, noting they’d “plugged up weaknesses on defense” and had “more scoring punch with men like Ralph Rogers and Phil Schmitt in there.” They started off strong, winning their first six games before losing to the Scalers. Claud Holsten, described as the “Dessert dead-eye,” scored 13 points in their first loss.

The Dessert All-Stars won the district A.A.U. playoffs at Gonzaga on February 21, 1936, and sought to take the northwest tournament crown denied to them the previous year. During the district playoffs, Holsten scored 54 points in three games. While they didn’t reach the championship game again, Holsten’s play was noted for his consistency. Due to changing circumstances in his personal life and the need to pursue a different line of work, Holsten left the team after the end of the 1936 season.

Following the end of his tenure with the Dessert All-Stars, Holsten was picked up by the baseball manager of the Silver Loaf Bakery team in the Eastern Washington League, Archie Buckley. Holsten also began playing for Silver Loaf Bakery’s eight-man basketball team. On January 8, 1937, Claud and Mabel welcomed their only child, daughter Gail Claudeen. Holsten played a season for the Spokane Indians minor league baseball team in 1939, where he was the team’s catcher. While he was at times described as “ragged defensively,” he showed “plenty of power at the plate.”

While Holsten’s athletic career wound down, he took a job with Old National Bank in 1936, a farm mortgage firm. He later worked for Vermont Loan and Trust Company in Spokane. Despite his athleticism and time as a semi-professional athlete, Holsten was noted to smoke around one pack of cigarettes per day. He was a member of the Spokane Elks, Travelers’ Club, Athletic Round Table, and Transportation club.

Wartime Service and Death

In the October 16, 1940 issue of the Spokane Chronicle, Holsten was interviewed about his registering under the peacetime military conscription law. He noted that he didn’t “favor this type of conscription, but don’t see what the country can do about it now. I think the government is about two years behind in this program.” Holsten was 31 years old at the time of his registration, and working at Vermont Loan and Trust Company. By the spring of 1941, Holsten began flying with R.G. Lamb at Felts Field in Spokane. He received instruction in a Luscombe A-65, where he did his first 35 hours of solo time. After that, he flew various planes, including a Cub J-5, Taylorcraft BC-65 Aeronca, Fairchild, and Luscombes. On August 10, 1941, Holsten purchased a Taylorcraft BC-65, which he flew until he had over 200 hours of flying time. While he didn’t have any mishaps while flying, he did have three forced landings with no damage sustained.

At the age of 33, in August 1942, Holsten applied for a commission to be a pilot in the U.S. Naval Reserve while he was enrolled in the Navy course for Crew Pilot Training (CPT) at Wallace Air School in Spokane. He’d logged 260 hours as a private pilot, with an additional 200 hours in the 12 months prior to his commission. He was eligible for Selective Service deferment, but he chose not to request it. The investigation for appointment in the Naval Reserve found that Holsten “should be exceptionally successful as an instructor due to the combination of leadership, outstanding ability in sports, business success and full training in civilian aviation.” He accepted an appointment on October 14, 1942 as a Lieutenant in the U.S. Naval Reserve, and reported to Naval Air Station (NAS), Corpus Christi, Texas on October 19, 1942 for training as a flight instructor.

Holsten did additional training beginning February 1, 1943 in New Orleans, before being assigned to NAS, Chicago, Glenview, Illinois as a Naval Aviator. On December 18, 1943 he reported to Civil Aeronautics Authority War Training School, Fairmont State College, in Fairmont, West Virginia. On January 1, 1944, he was appointed Lieutenant A-V (T). He was assigned to the Civil Aeronautics Authority War Training School at the University of Georgia as a Flight Supervisor on April 20, 1944, follow by a transfer to ACORN (Aviation Construction Ordnance Repair Navy) Assembly and Training Detachment, Port Hueneme, California on October 14, 1944. An ACORN unit consisted of an airfield assembly team designed to “accomplish the rapid construction and operation of a land plane and seaplane advance base, or in conjunction with amphibious operations, the quick repair and operation of captured enemy airfields.” An ACORN unit operated the control towers, field lighting, aerological units, transportation pools, and communication and medical facilities. They often operated in conjunction with a Naval Construction Battalion, known as “Seabees,” whose job it was to build airstrips, docks, roads, and other buildings.

Holsten received assignment to ACORN 47 on December 14, 1944 for duty involving flying and establishing a forward base outside the continental United States. ACORN 47 was the advanced party to build an airbase on the island of Palawan in the southwest province of the Philippines. They arrived in Palawan roughly around March 1945. Palawan was the site of Prisoner of War (POW) Camp 10-A, where American prisoners were sent in August 1942 to help build an airfield for their captors. The prisoners were treated horrifically, suffering both physical abuse and malnutrition as well as next to zero medical care. 159 American POWs from Palawan returned to Manila in September 1944, with 150 men remaining. On October 19, 1944, American bombers sank two enemy ships and damaged several Japanese planes on Palawan. The Americans continued to press on and destroy enemy aircraft on the ground, while the Japanese reluctantly allowed them to paint “American Prisoner of War Camp” on the roof of their barracks.

On December 14, 1944, Japanese aircraft misreported the presence of an American convoy, thought to be headed toward Palawan. The POWs were ordered into air raid shelters they had constructed, where they were closely guarded by their captors. 50 to 60 Japanese soldiers, under the leadership of First Lieutenant Yoshikazu Sato, began dousing the wooden air raid shelters with buckets of gasoline and set them on fire; they followed this up with tossing hand grenades into the shelters. For the men who were able to escape the fiery infernos, Japanese guards hunted and summarily executed them. Of the 150 American POWs, only 11 survived the massacre.

Holsten arrived on Palawan after American troops liberated the island. He spent much of his time flying officers around the Philippines to obtain updated classified code lists and photo supplies. He remained there even after Japan surrendered and the war in the Pacific officially ended. On September 10, 1945, Holsten departed in a TBM-1C Avenger on a routine flight from Palawan airstrip to Dumaguete, Negros, Philippines. The weather looked good, and the flight time estimate was two hours. Three other men were on board: Henry Ansell Newton, Aviation Machinist Mate, 2nd Class; William Edward Springer, Seaman, First Class; and Mitchell Mansfield Thrower, Aviation Machinist Mate, First Class. The plane and its occupants were never seen or heard from again. Despite an extensive search, neither the aircraft nor crew was ever found.

On September 18, 1945, an order was issued to Lt. Claud Holsten, directing him to report for transportation to Seattle, and from there to “proceed to his home for separation from active duty.” Mabel Holsten received word via telegram on September 25, 1945, her husband was reported as missing in action. She also received a letter from his commanding officer, relating Holsten’s service and loss.

Postwar Legacy

Holsten’s official date of death is listed as September 11, 1946, as those declared missing in action are not considered deceased until one year after their disappearance. He is memorialized at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines as well as the WSU Veterans Memorial. He was posthumously awarded the World War II Victory Medal in 1947 and the American Area Campaign and Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medals in 1948. He also received the Philippine Liberation Ribbon.

Following Holsten’s death, his wife, Mabel, worked as an elementary school teacher before her marriage in 1952 to William A. Davenport, a lawyer with Witherspoon, Kelley, Davenport, and O’Toole in Spokane. She died in October 1989 at the age of 80. His daughter, Gail, attended the University of Washington after graduating from Lewis and Clark High School in Spokane. She married and had two children, but died in a tragic house fire in 1995 at the age of 57. Her teenage son escaped without serious injury.