Billy Dean Hughes

Pre-WSC Years

Billy Dean Hughes was born William Dean Hughes on March 2, 1920, to Bland and Gladys Hughes in American Falls, Idaho. Hughes was his parents’ first child; his brother, Harold, was born two years later. The town of American Falls was first settled by Euro-American trappers at the beginning of the nineteenth century on the West bank of the Snake River. According to the history of the town provided by the Power County Historical Society, a party of American Fur Company trappers was floating down the Snake River in 1811 when they ran into turbulent waters at what is now American Falls, sending them careening over and into the water. They escaped injury, but most of their supplies and trading items were either lost or damaged. Others who passed by “The Falls” included the Whitman-Spalding missionary party in August 1836 and John C. Fremont in 1854.

The original town of American Falls today resides partially submerged under a reservoir. In 1925, the Bureau of Reclamation began work on the American Falls Dam, requiring the town itself, including nearly 350 residents and their homes, along with over 60 businesses, churches, and schools, to move across the river to prepare for increased water levels. The Oneida Milling and Elevator Company’s grain elevator remained behind, and today its 40-foot-deep foundation and 106-foot reinforced concrete walls still stand, it's top rising above the water.

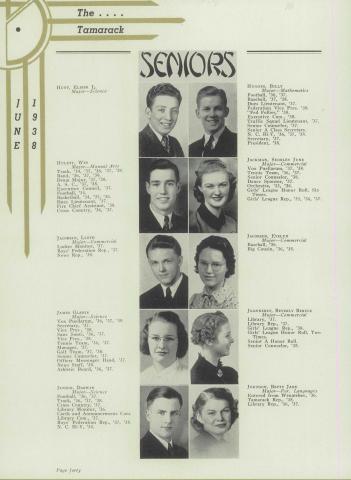

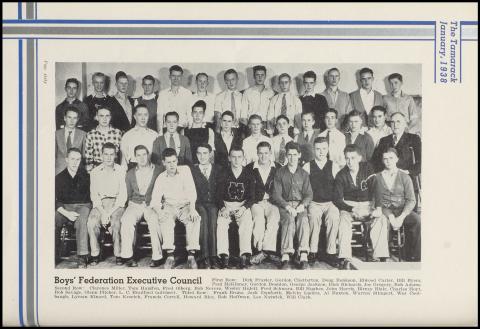

Bland Hughes moved his family to Spokane in 1930, where he built the Broadway Tavern. He was also associated with the Brown Derby, the Capitol in Hillyard, and the Purple Sage. He also owned and trained horses. Billy Hughes first attended Rogers High School in Spokane before transferring to North Central, where he left a mark in several extracurricular activities. He participated in the Traffic and Grounds Squads, ensuring students got to school safely. He achieved the rank of Traffic Squad Lieutenant. He also served on the Boys’ Federation Executive Council, and during his senior year was elected vice-president of the organization during the spring election. The Boys’ Federation promoted extra-curricular activities among the boys of the school, such as community service projects, personal service, school service, and vocational department functions. Hughes served as junior class secretary and Senior A Class Secretary.

Hughes belonged to the North Central Hi-Y, which was the high school’s YMCA organization. He also participated in athletics, playing both baseball and football. He was a pitcher for Rogers High School his freshman year. After transferring to North Central, he played football in his sophomore and junior years. He played outfielder for the North Central baseball team under Coach Archie Buckley, another Fallen Cougar. During his junior year, Hughes carried a .400 batting average to help North Central score pivotal victories against Gonzaga and West Valley. At the beginning of his senior year baseball season, Coach Buckley was quoted in the Spokane Chronicle as being “dubious” about whether Hughes and a few of his teammates could “make the grade.” However, Hughes received his letter in June 1938. He graduated from North Central in June 1938, with a major in mathematics.

WSC Experience

Hughes attended Washington State College (WSC) from 1938 through 1941 as a Speech major. During his freshman year, he was nominated to his class’s executive committee, a part of student government. He continued to participate in student government throughout his time at WSC and was nominated for junior class treasurer. He joined Phi Delta Theta, a fraternity founded in 1848 at Miami University and based on the three pillars of the cultivation of friendship among its members; the acquirement of a high degree of mental culture; and the personal attainment of a high standard of morality. Senator John McCain and astronaut Neil Armstrong were both Phi Delts. Hughes tried his hand at the theater during his college years, starring in Clifford Goldsmith’s play, “What a Life,” in January 1941.

Hughes registered for the draft on July 1, 1941, at which time he noted he was working as a temporary employee at Western Pine Manufacturing, a lumber company, in Spokane. He married 17-year old Ann Alethea Hughes prior to joining the United States Army Air Corps in December 1941. Their son, Thomas Bland Hughes, was born on May 24, 1942.

Military Service and Death

Hughes joined the United States Army Air Corps as an Aviation Cadet on December 19, 1941. He was part of the first class of aviation cadets to enter the air corps replacement training center at Kelly Field, Texas following the United States’ entrance into World War II. Kelly Field, located in San Antonio, Texas, was the home of the Advanced Flying School during World War II, graduating almost 7,000 men between 1939 and 1943. Following his graduation from the Advanced Flying School, Hughes went to Midland Army Air Field, the home of the United States Army Air Forces bombardier-training base. The first group of cadets arrived for training on February 6, 1942, and by the end of the war, the base graduated 6,627 bombardier officers. A newspaper photo from August 1, 1942, reveals Cadet Bill D. Hughes holding two puppies with the “bombsight eye, dark imprint of bombardiers,” mirroring the look of Bombsight Bessie, Midland army flying field mascot.

Hughes received his commission as a Second Lieutenant while at Midland, graduating as a bombardier. He was assigned to the 307th Bomber Group, Heavy, 424th Bomber Squadron. The 307th was activated in 1942 by the Army Air Corps Combat Command following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Beginning on April 15, 1942, they began operations as a B-17 Flying Fortress bomber unit at Geiger Field, Spokane, Washington. Its primary mission was to guard the northwestern United States and Alaskan coasts against an armed invasion, which helped prepare them for the unit’s later role in the Pacific Theater of World War II. The 307th’s B-17s were replaced with B-24 “Liberators,” and the unit transferred to Sioux City, Iowa for a brief training period before heading to Hamilton Field, California, then Oahu to begin search and patrol missions over the surrounding Pacific.

The 307th’s first combat experience occurred beginning December 27, 1942, when twenty-seven of the group’s aircraft were deployed to Midway Island. From there, B-24s staged their first attack on an enemy fortress at Wake Island, 1260 miles away. The 307th was able to blast 90 percent of the Wake stronghold, and all aircraft returned safely from what was considered “the longest mass raid of that time.” This, and other long-range missions, gave the 307th Bombardment Group their nickname, the “Long Rangers."

The 424th Bomber Squadron of the 307th to which Hughes was assigned trained at Sioux City, Ephrata Army Air Base in Washington, and Geiger Field. Following Hughes’ graduation from Midland in August 1942, he likely arrived at Dillingham Airfield in Hawaii on November 2, 1942. His squadron took part in the Wake Island operations from Henderson Field, Midway Atoll, from December 22, 1942, to December 24, 1942. The next operated from Funafuti Airfield, Nanumea, the Gilbert Islands from January 20, 1943, to roughly February 1, 1943, then Luganville Airfield, Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides from February 6, 1943, to about March 18, 1943. During their time at Luganville, many of the 307th began moving to Guadalcanal in February 1943.

From their new location, the largest of the Solomon Islands, the 307th attacked fortified Japanese airfields and shipping installations throughout the Southwest Pacific. They were assigned to the 13th Air Force, and the group would serve in combat missions for the rest of the war. The group’s time on Guadalcanal began with “two costly strikes” on the Russell Islands in advance of an Allied invasion on February 21. Fifteen aircraft took part in the two unescorted, daylight raids, with five losses. The group then moved to night operations, including an attack on airfields on Bougainville on March 20 to 21. The objective of the Solomon Islands campaign was to cut off Japan’s major forward air and naval base at Rabaul, on the island of New Britain. Rabaul was the centerpiece of Japanese air power in the South Pacific. Bougainville was a key component of this, although in the first part of 1943 air attacks were all that Allied troops could do.

The only accountings of Hughes’ death are surviving newspaper articles revealing he died somewhere in the South Pacific in a plane accident on April 29, 1943. Two weeks later seven B-24s would attempt to bomb Wake Island from Midway, and it is highly likely that Hughes’s accident occurred while preparing for that mission. He was 23 years old at the time of his death.

Postwar Legacy

On May 13, 1943, the Spokane Chronicle ran a small article announcing Hughes’ death, and noting that he had sent his son the Air Medal he’d received for gallantry. Young Thomas Hughes and his 18-year old mother, Alethea, won the Chronicle’s Father’s Day letter contest the following month. The letter, titled, “My Dad Is Doing a Job for Uncle Sam,” won Thomas a $25 War Bond. Through his mother, he wrote, “I am very proud to know that he is a war hero who died in the service of his country. I know wherever he may be – he is still pulling with all the boys in the armed forces.”

Hughes was posthumously awarded the oak leaf cluster in lieu of an additional air medal the following year for “meritorious achievement while participating as bombardier from February 15 to March 1943, in sustained combat operational missions.” Hughes is memorialized at the Tablets of the Missing, Manila American Cemetery in The Philippines as well as on the WSU Veterans Memorial.

His wife, Ann Alethea, remarried in November 1945, and his son grew up using the name Thomas Hughes Parsons, the last name of his stepfather. He died on June 12, 2001.