Robert Mitchell Ford

Pre-WSC Background

Robert Mitchell Ford was born on July 25, 1920, in Pullman, Washington. He was the son of his parents, James and Laura Ford, and was born into a large family. Robert was the fourth child of an eventual total of six children. His siblings included three brothers, James, Henry, and Jack, as well as two sisters, Marion and Betty. The Ford family lived in the town of Asotin, a small community south of Clarkston on the Snake River. The father, James, was the breadwinner for the family as he worked as a foreman at a lumber mill. Not much is known about Robert’s early life or where he attended high school. He likely graduated in the class of 1938 before enrolling at Washington State College later that fall.

WSC Experience

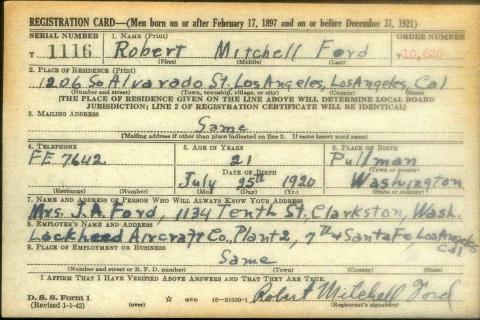

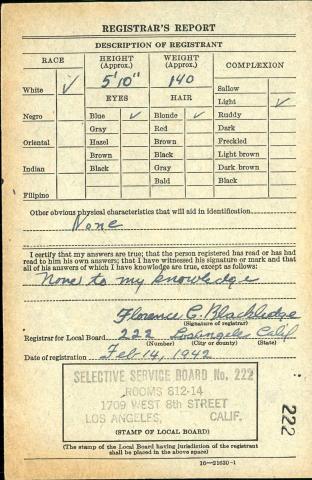

Robert Ford’s time at Washington State College was brief and does not provide many sources. He only attended school for a single year from 1938 to 1939 and was listed as an English major. In that one year, Ford lived in Waller Hall, a men’s-only dorm located on campus. After his only year at WSC, Ford returned back to his parent’s home in Asotin to work. It is unknown why Ford’s time in college was so brief, one may speculate that it was perhaps because college was too expensive or that it simply did not provide Ford with what he thought it could. Nevertheless, Ford returned to Asotin for some time and worked as a box setter at a local box factory, according to the 1940 Census. The next two years are not documented well as they offer no indication as to what Ford was doing or when he decided to move to Los Angeles, California. With war breaking out in December 1941, there were many new jobs created to assist in the war effort to manufacture vehicles needed to equip the military. In southern California, the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation was among the many companies that were searching for workers to help satiate the demand for aircraft and the lure of a good job likely drew Ford to make the move south. A military registration card dated February 14, 1942, lists Ford as a worker for Lockheed and residing in Los Angeles. Ford also lists his mother as a contact, pointing to Ford still being an unmarried bachelor at the time. Despite being registered for service, there is evidence to suggest that Ford did not begin his military service until 1944.

Even though Ford did not immediately begin serving in the armed forces, he was still doing his part for the American war effort. American manufacturing was crucial in the success of the US military waging a two-front war in Europe and the Pacific. Ford’s work at Lockheed helped to assemble aircraft that gave the US an edge in the skies over their enemies. In 1944, Ford was on a voter registration list for Los Angeles County as a registered Democrat and still an aircraft worker. As 1944 was coming to a close, Ford enlisted for duty on September 2. By the time he enlisted, he still claimed that he was single with no dependents at the time. As an enlisted man with no training, he began his military career as a private. Instead of serving to build machines of war, Ford now began to serve as one of the millions of men fighting to finish the conflict.

Wartime Service and Death

When Ford departed for combat overseas, he was joining a unit that was seasoned with action across the Pacific. Ford was attached to Northern California’s 184th Infantry Regiment, which was part of the 7th Infantry Division. The men of “Let’s Go” 184th were a seasoned unit that had been deployed in unique battlefields in the Pacific. The first deployment was in August 1943 on Kiska, an island that was part of the Alaskan Aleutian Islands and holdout of the last Japanese troops on American soil. The Japanese evacuated the island before the Americans landed, stealing the 184th of its first taste of battle. The 184th soon had another opportunity to meet the Japanese in combat as in February 1944, they were assigned to take Kwajalein Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands. The operation was successful, as the regiment helped to neutralize the heavily fortified island that was manned by 8,000 Japanese defenders. After resting on Hawaii, the 184th participated in the invasion of the Philippines in October 1944, landing on the island of Leyte. The 184th fought against several battle-hardened Japanese divisions and performed well in combat as they had in Kwajalein. The unit was eventually relieved in February 1945 in preparation for participation in the Battle of Okinawa. It is unknown if Ford ever saw action with the 184th on the Philippines or if he saw brief action towards the end of the campaign. Regardless of his combat experience, Ford and the rest of the men in the 184th prepared themselves for the hard, bloody fighting that would follow on Okinawa.

When US soldiers landed on Okinawa, they were stunned by the lack of Japanese resistance that greeted them. Instead of preventing an amphibious landing on the island, the Japanese forces on Okinawa entrenched themselves in areas to the south that were more easily defensible. As the 184th ventured further south to find their foes, the Japanese opened a whirlwind of fire from fortified defensive lines. Battles for small objectives incurred a heavy cost of men, as thousands became casualties trying to uproot the stubborn Japanese soldiers. By May 22, American troops had made progress and were targeting the Japanese headquarters at the Shuri Castle for their next objective. Unfortunately for the troops, the Okinawan monsoon season began and the torrential rains created mud that slowed the operation. On May 27, Ford was advancing upon a Japanese position and started to lay down suppressive fire with his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), helping his platoon clear out the fortification. As the men regrouped in the position, Ford was shot by an enemy sniper, mortally wounding him. He died of his wounds only a few minutes later, killed in action at the age of twenty-four. Less than three months later, Japan surrendered and ended the Second World War with an Allied victory.

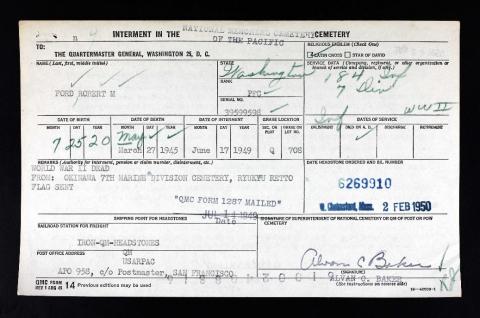

News of Ford’s death took little time to arrive back to his loved ones in the states. His parents received the news, as well as his wife, Mary D. Ford, and newborn daughter, Lorene Christine. It is not known when Ford got married, but it was likely sometime between his enlistment in the Army and deployment overseas. After news of Ford’s death arrived, his wife and parents received a letter from Captain Herbert M. Reiman that explained further the cause of his death. In regards to Ford, he stated, “Although he had not been with this Company for any great length of time his cheerfulness made him one of the best-liked men we had,” and that he was a “gallant soldier.” Ford was initially buried at the 7th Marine Division Cemetery on Okinawa, but his body was later reburied at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. Even though he only attended WSC for a single year, Ford’s name was added to the WSU Veteran’s Memorial alongside every WSC student who fell during the war.

Postwar Legacy

Although Ford’s legacy as a student of WSC and soldier during the Pacific War were limited in length of time, his commitment to the war effort and personal legacy stretch much further. Ford journeyed far from his home in Asotin to live in California, working to build crucially needed aircraft to fight the war for years before he enlisted. On the battlefield, his short amount of time with his comrades earned him their respect, helping to pave the way for an American victory on Okinawa. But the most lasting legacy he left was with his own family, as he was a father that left behind a loving wife and daughter because of his sacrifice on the battlefield.