Maximo Paulino Sebastian

Pre-WSC Background

Maximo Paulino Sebastian was born in the municipality of Jones, in the coastal province of Isabela, roughly 248 miles from Manila, Philippines. The available records for Sebastian reveal his year of birth to be different on each document; a Washington Passenger and Crew List for the arrival of the ship, President Lincoln, in Seattle in July 1930 lists his date of birth as November 18, 1909. His United States World War II draft card shows his date of birth to be November 18, 1912. At the time he completed his draft card, Sebastian listed his age as twenty-eight, which corresponds with the 1912 date. For the purposes of this biography, the date of birth to be used is November 18, 1912. The names of Sebastian’s parents are unknown.

The province of Isabela was created by royal decree on May 1, 1856, in order to facilitate the work of missionaries in their efforts to evangelize the Cagayan Valley; the new province was named Isabela de Luzon in honor of Her Royal Highness Queen Isabella II of Spain. Following the Philippine-American War (February 4, 1899, to July 2, 1902), a civil government was established in Isabela with Captain William H. Johnson appointed as the first American governor. However, many nationalists continued to rebel against the American presence for several years. The town of Jones was originally called Barrio Cabannuangan, but the name was changed on January 1, 1921, in honor of U.S. Congressman William Atkins Jones, the author of the Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916. Early inhabitants in the area grew tobacco and corn as the primary crops.

Sebastian graduated from high school in Jones.

WSC Experience

Sebastian arrived in Seattle in July 1930 following his graduation from high school. It is unknown where he lived after he came to the United States, but during 1933 to 1934 academic year he was listed in a Directory of Filipino Students in the United States as attending Yakima Valley Junior College. Washington State College (WSC) had a Filipino Club during the 1920s and 1930s, and records from those decades reveal several Sebastian's from Jones, Isabela Province attended the college. It is highly likely that Maximo Sebastian followed the path forged by his family members by attending WSC after his time at Yakima Valley Community College. In addition, it appears that these young men were likely influenced by Christian evangelist movements that sought to bring students from Asia over to the United States to study.

The Filipino Student Christian Movement (FSCM), the publisher of the directory in which Sebastian was listed, was part of the YMCA’s Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students. The group was established in 1923 and grew out of a tradition of Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese Christian college students coming to the United States to study at West Coast universities with the assistance of Christian organizations. For Filipinos, the Pensionado Act of 1903 provided U.S. government-funded scholarships to the sons and daughters of elite Filipinos who often held positions in the American colonial government. However, students weren’t treated as elites in the United States and were often met with anti-Asian sentiment, discriminatory measures, and racism on and off-campus. In Pullman, townspeople threatened to pull funding from an International House run by the YMCA if it did not evict its Filipino residents. An article in the Spokesman-Review published on March 5, 1930, revealed a Spokane County Deputy County Auditor refused to issue a marriage license to a “well-groomed Filipino and a pretty white woman, both in the 20s.” The young couple was thought to be affiliated with WSC, but WSC denied any knowledge of a relationship between any Filipino men and white women.

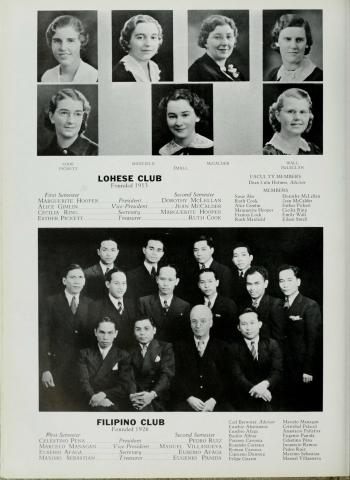

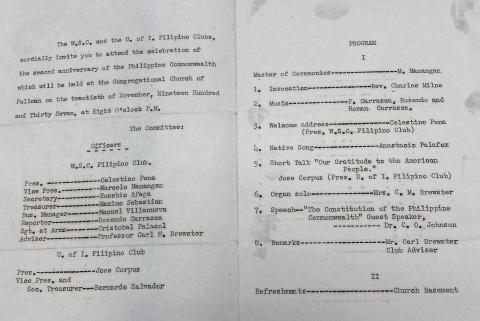

Despite such occurrences, the FSCM and other Christian organizations addressed racism on campus and in the communities in which they lived. They held student conferences and contributed to student publications. They also built large, pan-ethnic networks to identify housing needs as well as promote more inclusive college curriculums. WSC’s Filipino Club was founded in 1926, and newspaper records reveal that the organization fielded competitive intramural volleyball teams as well as providing a place for students to help each other navigate their studies.

Sebastian attended WSC from 1935 to 1937 as an Education major. He joined WSC’s Filipino Club, where he was elected the organization’s treasurer. At some point, Sebastian transferred to the University of Idaho, and in 1940 he listed his home address in Moscow, Idaho on his draft registration card. He also listed Mrs. Marie Brown as his guardian. He completed his degree at the University of Idaho, then moved to Iowa to pursue a graduate degree in Education at the University of Iowa.

Wartime Service and Death

Sebastian was considered “lost” in November 1942; he was on a list of men who had not notified the county selective service office of their whereabouts. A newspaper article published on November 6, 1942, noted that he and other men considered “lost” would be turned over to the FBI. However, by that point, Sebastian was likely attending the University of Iowa. Following the declaration of war against Japan on December 8, 1941, and the Japanese invasion of the Philippines that followed, Sebastian lost all contact with his family in Jones, Isabela. He entered the United States Army in 1944, and records reveal he was a Technician, Fifth Grade. A Technician Fifth Grade, or T/5, was a United States Army technician rank during World War II. Those who attained this rank were addressed as “Corporal,” but they did not possess the authority to give commands as a corporal would.

By the summer of 1944, American forces had reached a point 300 miles southeast of Mindanao, the southernmost island in the Philippines. They now stood at the “inner defensive line of the Japanese Empire,” and the construction of airfields in the Marianas allowed US Army Air Forces within striking distance of the Japanese home islands for the first time during the war. Airstrikes against Japanese airfields on Okinawa, Formosa, and Luzon, as well as enemy shipping in adjacent waters, took place in October 1944. Because of the success achieved in this campaign, the Joint Chiefs of Staff felt that a major landing on Mindanao was not necessary and all “available shipping and logistical strength could now be concentrated on Leyte.” They directed General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to cancel intermediate operations and fast-track planning to carry out an invasion of Leyte on October 20.

Leyte is one of the larger islands in the Philippines, with deep-water approaches on the east side of the island along with sandy beaches providing opportunities for amphibious assaults and resupply operations. The interior of the island contained a “heavily-forested north-south mountain range, separating two sizable valleys…” On October 20, 1944, the U.S. Navy landed four Sixth Army divisions ashore on Leyte. Japanese aerial counter-attacks damaged the USS Sangamon and a few other ships but did not prevent the landings. Later that same day, General MacArthur gave his “I have returned” radio message to the Philippine people.

Shortly after the American forces landed, the Japanese sent a formidable naval force to the islands. From October 23 to October 26, the “greatest naval battle of World War II” took place. During the early morning of October 25, 1944, four Japanese battleships, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers surprised the Allies, sinking four ships: the USS Gambier Bay, USS Hoel, USS Johnston, and USS Samuel B. Roberts. Despite these losses, the Japanese suffered heavy losses and decided to withdraw. Kamikaze suicide planes were engaged and sank the USS St. Lo and damaged others. It is unknown which of these ships Sebastian was on, but the report of his death indicates the “landing ship on which Technician Sebastian was being transported was destroyed when a Japanese plane scored a direct hit,” on October 25, 1944.

Postwar Legacy

It is unknown if Sebastian’s body was recovered. He is not listed in the American Battle Monuments Commission, and it is unknown if he is memorialized in his hometown cemetery. He is, however, memorialized on the WSU Veterans Memorial.