Arnold William Erickson

Pre-WSC Background

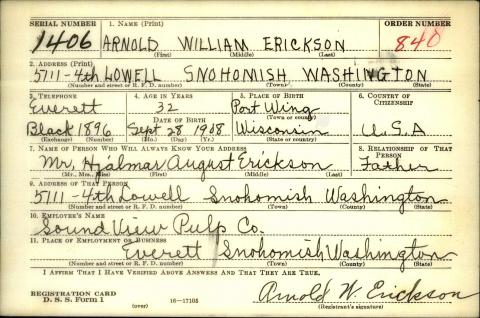

Arnold William Erickson was born on September 28, 1908 in Port Wing, Wisconsin, the second son of Hjalmar August and Albertina Westlund Larsdotter Erickson. His older brother, Roy, was born in December 1907, and his younger brother, Harold, was born in March 1910. Both of Erickson's parents were immigrants from Sweden. Hjalmar was from Falun, a city in central Sweden's Dalarna County, and he arrived in New York via Göteborg on September 27, 1901. Albertina was born in Hosjö, also in Dalarna County, in July 1882 and she came with her family to the United States in July 1888. Hjalmar and Albertina married on June 18, 1905 in St. Louis, Missouri.

Hjalmar worked as a laborer at a lath mill and the family lived in Port Washington, Wisconsin while Erickson and his brothers were small. Port Washington was a prosperous manufacturing city by the end of the nineteenth century thanks to a reliable source of water generating power for industry and having an open harbor for transport vessels. However, in 1899 a fire destroyed almost half the town. Despite this tragedy, the town rebuilt and today has the largest collection of pre-Civil War buildings in Wisconsin. By 1920, the Erickson family relocated to Lowell, Washington, in Snohomish County, where Hjalmar continued to work as an operator at a lath mill.

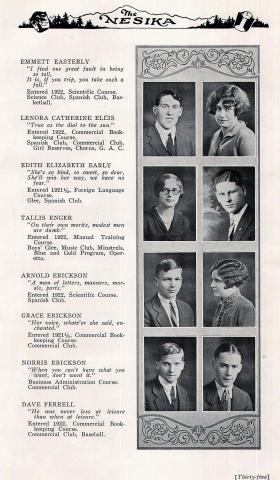

Erickson attended Everett High School, which when it opened in 1910 served a large number of immigrants from Sweden, Norway, and Germany. He graduated in 1926. The Everett Nesika yearbook for 1926 revealed Erickson had taken a scientific course in high school, and that he was a member of the Spanish Club. The quote attached to his name read, “A man of letters, manners, morals, parts." World War II would claim the lives of more than 100 former students of Everett High, including Margaret Billings, an Army nurse killed in 1945 aboard a ship attacked by a kamikaze pilot in the Pacific theater. She is believed to be the only woman from Snohomish County killed in World War II. She graduated two years after Erickson.

WSC Experience

Erickson attended Washington State College (WSC) from 1928 through 1932, earning his BS in Chemistry in 1932. He also earned his MS in Chemistry at WSC on June 5, 1933 according to school transcripts; however, his degree was noted in the 1934 commencement program. His thesis was titled “The Electrolytic Reduction of Nitrophenetole." Erickson lived in Stimson Hall, a men’s dormitory, during all four of his undergraduate years. As a resident of the hall, he was also a member of the Montezuma Club, which was the main governing body for Stimson Hall. He also served on the Senate Club for Stimson. His brother, Harold, would join him as member of the Senate during his (Arnold’s) senior year. During his junior year, Erickson was initiated into Phi Lamba Upsilon, the national chemical society.

Following the completion of his Master's degree, Erickson returned home to Lowell where he worked as a chemist for Everett Pulp and Paper Company and Soundview Pulp Company. He was living with his parents at the time of the 1940 United States Federal Census.

Wartime Service and Death

Erickson registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, then enlisted in the United States Navy at the age of 34 in September 1942. He did well during his training courses, rating 38 out of 240 sailors; he also did well as a marksman, scoring 131 out of a possible 150 and firing 30 rounds of ammunition. He trained as a radio technician, a position responsible for transmitting and receiving radio signals and “processing all forms of telecommunications through various transmission media aboard ships, aircraft and at shore facilities." Navy radiomen were often given the nickname "Sparks" due to the four lightning bolts on their insignias, and they learned Morse code, USN communication, and radio theory. Erickson attended training at Radio School in Bremerton, Washington; Pre-Radio Materiel School in Chicago, Illinois; Navy Technical School (Elementary Electricity and Radio Materiel) in Queens College, Grove City, Pennsylvania; and Navy Technical School in Treasure Island, California. Treasure Island, connected by a causeway to Yerba Buena Island and collectively known as the U.S. Naval Training and Distribution Center in San Francisco, saw as many as 4,500,000 “of the world’s finest fighting men” pass through during World War II on their way to service overseas.

Erickson was assigned to the USS Cassin Young, a destroyer built for speed by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation in San Pedro, California in 1943. She was one of 175 Fletcher-class destroyers built during World War II, and she was commissioned on December 31, 1943. She departed San Pedro on March 10, 1944 and arrived in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on March 19, 1944. Beginning on April 29, 1944, Cassin Young attacked Japanese strongholds in the Caroline Islands, an archipelago in the western Pacific. A war diary for the Cassin Young reveals an entry dated April 29, 1944, recording the destroyer’s first combat engagement experience, “TF-58 operated offensively in an area south of Truk against Japanese air and surface forces, and shore installations in and about the Caroline Islands, concentrating on Truk, Woleai, Satawan and Ponape…Throughout the day scheduled air sweeps and strikes were launched with no enemy opposition over the Task Group." In June 1944, the ship escorted American amphibious forces during the invasions of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Mariana Islands.

On June 15, 1944 the Cassin Young rescued four aviators forced to land in water as a result of damage sustained to their plane over Saipan. While doing so, they faced enemy fire, with one Japanese “torpedo plane observed making a run” so the destroyer opened fire at the plane. The enemy aircraft was shot down by “friendly fighters.” On June 17, 1944, just prior to dark, a group of enemy planes was detected coming in from the south, and the Cassin Young soon experienced an attack by Japanese Dive Bombers. Due to confusion caused by darkness, “unfortunately a number of friendly planes were fired upon by vessels of this TG." However, it does not appear that any planes were shot down and the crew were able to rescue a fighter pilot by the name of Lieutenant Murphy.

An interesting entry on June 26, 1944 reveals how Japanese aircraft used radar deception to avoid detection in the Tinian channel; however, none came within gun range. Throughout the rest of the summer of 1944 the daily reports provide evidence of the continual specter of Japanese planes in the Cassin Young’s vicinity, but it would be October before the crew participated in the Battle for Leyte Gulf. From October 12 through 14, 1944, the crew faced enemy attacks “on and about” Formosa and Pescedores Islands, with several personnel receiving shrapnel wounds from low-level attacks on the 14th. None of the wounds were fatal, and the ship sustained just superficial damage. On October 23, 1944, the War Diary notes the Cassin Young was on its way to an operating area east of the Central Philippines.

On October 20, 1944 the U.S. Navy landed four Sixth Army divisions ashore on Leyte. Japanese aerial counter-attacks damaged the USS Sangamon and a few other ships, but did not prevent the landings. Later that same day, General MacArthur gave his “I have returned” radio message to the Philippine people. Shortly after the American forces landed, the Japanese sent a formidable naval force to the islands. From October 23 to October 26, the “greatest naval battle of World War II” took place. The Cassin Young took part in several actions connected to this historic battle. She rescued over 120 men from the burning and sinking U.S.S. Princeton on October 24, and participated in the Battle of Cape Engano the next day. Four Japanese carriers were sunk by the American carriers the Cassin Young escorted. The destroyer continued to escort carriers providing air cover to American troops fighting for the liberation of the Philippines throughout the remainder of 1944.

On November 5, 1944, while providing escort off Luzon in the Philippines the Cassin Young experienced their first encounter with kamikaze fighters. Suicidal crashes into enemy targets, usually ships, became prevalent after the Battle of Leyte Gulf until the end of the war in the Pacific theater. By the end of the war, kamikaze attacks sank 34 ships and damaged hundreds of others. On November 5, the Cassin Young reported that the U.S.S. Lexington was hit “on the starboard side in the vicinity of the bridge by a crash diving enemy plane..." The vessel also faced worsening weather and a typhoon in the following days. On November 14, 1944 the crew rescued Ensign Allen Brody, U.S.N.R. but were unable to find any trace of his two crewmen. On November 25, 1944, the Cassin Young reported the U.S.S. Essex sustained repairable damage due to an “enemy suicide dive."

In January 1945, the task group to which Cassin Young was assigned set out to sea for attacks against Formosa, Indochina (present-day Vietnam), and southern China. This set the stage for the coming invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. On February 19, 1945, the destroyer noted the Task Group “swung into the wind and the carriers commenced launching planes to support landing forces on Iwo Jima." The Cassin Young conducted maneuvers to confuse enemy attacks and created smoke screens. Several days later, the vessel made its way toward Honshu Island, the largest and most populous main island of Japan. By March 1, 1945, Cassin Young was reassigned to Task Force 54, the gunfire and covering force for the invasion fleet of Okinawa.

The Battle of Okinawa took place from April 1, 1945 through June 22, 1945; it was the last major battle of World War II, and one of the most brutal. On Easter Sunday, April 1, the Navy’s Fifth Fleet and more than 180,000 U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps troops descended on Okinawa for their final push towards Japan. The stakes for Okinawa were exceedingly high, as an Allied victory here meant that Japan would likely fall. Securing the airbases on the island was imperative to launching an invasion of Japan. American troops were able to land on Okinawa's beach with little resistance, as the Japanese command ordered their troops not to fire but instead wait for their enemy to come inland. The Cassin Young performed the duties of a radar picket ship providing early warning of impending air attacks to the main fleet. At sea, on April 4, 1945 the Japanese unleashed kamikaze pilots on the Fifth Fleet.

It would be on April 6, 1945 that the Cassin Young began heavy engagements with enemy aircraft. The Japanese sent 355 kamikazes and 341 bombers to Okinawa. A War Diary entry notes, “Drove away an approaching enemy plan by gun fire…Enemy air activity increased during the afternoon…The combat air patrol assigned this station intercepted and shot down planes during the day." The destroyer fired at a sinking ship, the U.S.S. Colhoun, at the request of its commanding officer in the event it was taken by the Japanese. The crew also rescued survivors from destroyers sunk by kamikaze.

The Cassin Young experienced a major attack on April 12; they managed to shoot down six kamikazes but one hit the mast and exploded fifty feet above the ship. One sailor died and 59 were wounded. It would be July before Cassin Young returned to Okinawa. During the Battle of Okinawa, the Fifth Fleet suffered 36 sunk ships; 368 damaged ships; 4,900 men killed or drowned; 4,800 men wounded, and 763 lost aircraft. On the island itself, Japanese troops and Okinawa citizens believed Americans did not take any prisoners, so thousands took their own lives. General Ushijima and his Chief of Staff, General Cho, committed ritual suicide on June 22, essentially ending the Battle of Okinawa. Both sides suffered devastating losses. 12,500 Americans were killed with 49,000 casualties; 110,000 Japanese soldiers lost their lives, and between 40,000 and 150,000 citizens on Okinawa died. Despite the battle being over, the Cassin Young remained in Okinawa.

Sixteen days before Japan’s surrender, on July 30, 1945 the Cassin Young War Diary notes of a bogey “could not be out-maneuvered." Roughly thirty seconds after the destroyer opened fired on the enemy aircraft, the “plane was seen on the starboard quarter diving at a position angle of 250. She hit the ship at the starboard boat davits, exploding and gutting the after bridge and main deck structures." Twenty-two men died and forty-five were wounded, including Arnold William Erickson; he was killed instantly at his battle station. The Cassin Young has the distinction of being the last ship hit by kamikaze within the vicinity of Okinawa. The destroyer was awarded the Navy Unit Commendation.

Postwar Legacy

In a letter to Erickson’s family, Commander John W. Ailes III wrote that they “who were his shipmates grieve with you at his loss. We all consider ourselves better for have (sic) served with him and known him…He was liked and admired by all of us. He truly served his country with distinction." A memorial for the twenty-two dead was held on August 5, 1945, and they were buried on Okinawa. Erickson’s remains were reinterred in Evergreen Funeral Home and Cemetery in Everett, Washington in 1949. Erickson is memorialized on the USS Cassin Young Honor roll at Boston National Historical Park Massachusetts and on the WSU Veterans Memorial.